by Dr. Ruth Berson

Why do you want to be a doctor?

The challenge posed by the personal statement for medical school is weird. On the one hand, you only have to write 5300 characters, about a page and a quarter single spaced. How hard can it be to write a page and a quarter when you have written 12-page or 20-page papers all through undergrad? But on the other hand, how can you condense why you want to be a physician into that limited space? Some students think back to the very first time they realized they wanted to be a doctor. Others are inspired to talk about what kind of doctor they want to become.

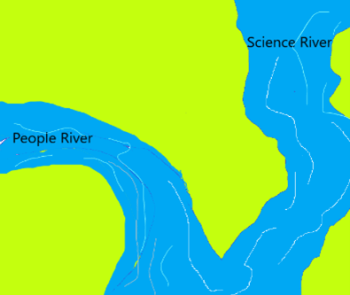

My view is that the field of medicine is at the confluence of two rivers – the people river, and the science river, and that medical schools would like to know what those two things mean to you. I believe medical school admissions committees wish they could implant a tiny chip in your head, so they could observe how you feel while you go about your pre-health activities involving people and science. The next best thing would be for you SHOW them how important people are, and how important science is, to you. How these two powerful rivers come together to carry you to the inevitable goal for someone who feels these passions: medicine.

Sounding like every other applicant

People, science; science, people. Won’t every applicant talk about that? Shouldn’t you write about something different? Something that will make you stand out?

You know how each snowflake is absolutely unique – no two are alike. And yet when you look out over a field of snow, or watch the flakes coming down from the sky, you can’t tell one from another. The medical school admissions committee are aware that each of you is unique, and yet when they look out over the field of you, what they mostly see is 22-year-old pre-meds, many of whom have gone to fairly elite colleges. How strange would it be to look out over a field of snow and see individual snowflakes waving their hats in the air shouting “I’m unique!” The med schools know each of you is unique. Rather than trying to prove the obvious, what you really want to do is show them your actual shape – not how your shape is different from the others, but the actual contours of YOUR shape. And a good way to do this is by telling them a story.

How to find a story – or rather, two stories

Because you are at the confluence of these two rivers, you need two stories – a people story, and a science story. These take time to find and polish.

Find a people story

We’re looking for a story that goes: I helped someone. I saw it had an impact. I felt gratified. So make a list of four or five times when you were in a caregiver role to someone, one-on-one – as a volunteer, a tutor, a teacher, a mentor, a coach, a babysitter. Doesn’t have to be related to medicine. The point is to show that you connected with someone, and got so much gratification from it that you would be willing to do it again and again for the rest of your life.

From the four or five times you listed, pick one. The challenge now is to find the moment right before you felt the wave of gratification. To do this, you may have to write the story out, or replay it in your head, or tell it to someone. Here’s an example of how telling it to someone might sound:

Student: So I volunteer at the hospital.

Me: Tell me about one patient, on one particular day. Where are you? What are you doing?

Student: I was wheeling a lady from her room to the X-ray room.

Me: Did you chat with her along the way? What did you talk about?

Student: We might have talked about the weather or something – I don’t remember.

Me: Did you wait with her in the X-ray waiting room until she was called?

Student: No, I had to go pick up someone else after I got her there.

Me: So when you said goodbye, did you get a sense of gratification from having fulfilled your role?

Student: (starting to remember more clearly) Actually, when I went around to the front of the wheelchair, the lady looked a little, sort of, huddled up, so I asked her if she was okay, and she said she was cold. So I asked her if she wanted a blanket and she said she did. So I went to the nurse’s station to ask where blankets are kept, and went and got one, and tucked it around the lady. And when she said thank you, I really got this sense of having done something valuable.

When you get to this point – where you can identify the moment right before the wave of gratification – stop for a minute. Put your pen down, or take your fingers off the keys. Close your eyes and imagine yourself into that moment. You are there. What can you see? What can you hear? Is there anything particular to taste, touch or smell? Take your time to look around and listen. Then open your eyes and write down the details.

Develop the story

Now we have the beginnings of the ‘hook’ of your personal statement. Look back at the blanket story above. What was happening right before the moment of gratification? To me it looks like the student tucked the blanket around the lady in her wheelchair. And let’s imagine ourselves there – what might we see, hear, taste, touch or smell? One thing I can imagining feeling is the nubbiness of the blanket, or whatever its texture is. Try starting with that as the hook, then backing up and explaining the situation and its importance to you.

I tucked the nubby white cotton blanket around the patient’s waist and shoulders and stood back to see if there was anything left uncovered. “Does that feel better?” I asked. She nodded. I checked once again to see that the wheelchair was locked, and started to say good-bye. “Young lady,” the patient said. I looked back at her. “Thank you,” she said.

OK – that’s the hook. It’s only interesting because it goes into so much detail that the reader feels something must be about to happen. And it is. You’re about to tell us what this ‘thank you’ is for.

I only met this lady about 10 minutes ago, when I picked her up from her room to take her to X-ray. Along the way we exchanged a few pleasantries about the weather and the hospital food. I didn’t really feel that much of a connection with her until we got to the X-ray waiting room, and I came around the front of the wheel chair to say goodbye to her. I noticed she looked a little huddled up in her chair. “Are you cold?” I asked her. She nodded. “Would you like me to go find you a blanket?” So I go and find a blanket, I come back, tuck the blanket around her, and that’s when she looks right at me and says ‘thank you.’ It gave me a sense that I had done something valuable.

Let’s look back at our opening one more time, and actually LIST the sensory details:

Sight: white blanket, lady looking huddled, her nodding, checking the blanket is tucked in all the way.

Feel: nubby, cotton; the lock settled down onto the wheel of the wheelchair, feeling of making blanket secure around waist and shoulders. The warmth of the blanket if it has been kept in a warming cupboard.

Hear: lady saying thank you; your own voice asking if she’s ok.

Why are the details important?

When you put in sensory details, you enable the reader to put themselves in the scene while the story takes place. They watch the action unfold, and through your eyes. Since you are the main character, they start to identify with you. Just as you may have understood how Harry Potter felt when he heard Hagrid bang on the door of the cabin on the rock in the sea, and saw him pull a teakettle and a frying pan out of his pocket, and smelled the sausages cooking, so will your reader understand what you are thinking and feeling as you go about the activities that qualify you for becoming a doctor –in this case ‘interacting with people’, but in a moment we’ll get to ‘thinking like a scientist’.

I get goose bumps when I retell this story. It ticks the boxes of the people story arc: helped someone. Saw impact. Felt gratification. And the details – the huddled look, the blanket – make it beautiful.

Find a Science Story

OK, we’re going to repeat the process, only this time the arc of the story is: I was doing something science-y. I solved a problem/got a result. I got gratification.

So make a list of science-y experiences: lab classes you’ve taken, or labs you’ve worked in, or any clinical work you’ve been allowed to do (taking blood pressure at a health fair), your favorite metabolic pathway, or discussing patient symptoms with a doctor you are shadowing.

Sometimes this helps: think about a time when, as a college student, you experienced science with the gee-whiz excitement of a little kid. “Golly, I added this powder and the whole thing turned blue!”

From this list, pick one experience to practice on. The goal again is to find the moment right before the wave of gratification. You may want to write the story out, replay it in your head, or tell it to someone.

Here’s an example:

Me: So, what kind of work do you do in your lab?

Student: Well, we’re looking for a way to do single-cell sequencing faster.

Me: What are you looking AT? Cells under a microscope?

Student: I’m look on a computer screen at numbers on spreadsheets.

Me: Oh. Oh, dear. Well, what are you looking FOR? How do you know when you have succeeded?

Student: I’m looking for 0.05. That shows that the thing that we found is statistically significant.

Me: So think of one occasion when you were doing this. How long had you been at it? How bored and cross-eyed were you? What other much more fun things could you have been doing with that time?

Student: I’d been doing it for hours. At first you think, any minute now I’ll see the 0.05. But after awhile when it doesn’t happen, you think, oh, well, I still have to go through all these numbers. And part of your mind goes on autopilot. It seems your whole life is just clicking down through the spreadsheet.

Me: And then what?

Student: Well, if you’re lucky, suddenly there’s 0.05. Maybe you almost miss it because your mind is glazed over. But no, there it is.

Me: And what does that feel like?

Student: Well, it’s immense. First of all, it means the work your lab is doing might actually have some meaning. And secondly it means you can stop scrolling through the spreadsheet. And you’re the one who discovered it. So it’s a great feeling.

Me: And where were you when this happened? Was it day? Night? Were you in the library? The lab? Your dorm room? Was it noisy or quiet?

Student: I was in the library, in a carrel on the 4th flour. All the carrels were full, I remember – it was around midterms. I looked up and saw that portrait of the lady in blue that hangs there, and I thought, lady, I could kiss your face. It was kind of an alive feeling.

Develop the story

Remember, you are looking for the moment just before the wave of gratification hits you. And then, as in the people story, let the reader identify with your feeling of gratification through their senses. Put yourself back in that moment. What DID you do when you realized what had happened? Perhaps you:

- Grabbed my phone and texted my PI/parents/roommate (tactile).

- Looked up and noticed that everyone else had left – or that it had gotten dark out (visual).

- Looked up and noticed there was a portrait of a famous donor looking down at me (visual).

- Shut my computer and did a little dance right there in the library (kinetic).

- Felt like a tiny bomb had exploded in my head (sound? Vibrations?).

And then, just as you did with the people story, use these sensory cues to create a scene right before the wave of gratification. Here’s my attempt:

It’s been hours since I found an empty carrel in the library and sat down to go over the data my PI sent me. Row after row of columns showing X (whatever it is), representing months of work on Y. At first you think, any minute now I’ll see the 0.05. But after a while when it doesn’t happen, you think, oh, well, I still have to go through all these numbers. And part of your mind goes on autopilot. It seems your whole life is just clicking down through the spreadsheet. And then suddenly there’s 0.05. Maybe you almost miss it because your mind is glazed over. But no, there it is. When I realized what had happened…

Notice that the part in italics is taken directly from the student’s conversation with me. Don’t stare at your computer trying to think of how to phrase something. Just tell it to someone and ask them to write down what you say.

I picked this story because it presents the greatest challenge – how can you dramatize something as boring as scrolling through an endless excel sheet looking for the figures 0.05? Most of the science-y activities students have told me about involved color, light, movement, smell, etc. Here are some examples:

- Petri dishes with more or fewer dots in them, depending on whether whatever agent was introduced caused growth or killed off cells

- Looking through microscopes at shapes and colors

- Drawing complex and multi-colored diagrams of systems to study for a test

- Explaining a concept to someone else another way (that can also be a people story)

- Solving a problem in a lab…going back over to see if an error was made, or testing the different elements – the temp, the proportions, the length of time…

- Solving a problem while building or fixing something – even a car engine.

- Any time you found yourself thinking like a scientist (observe, hypothesize, test, repeat)

- Going through a differential diagnosis sequence of thought

- A time when you put two and two together in your mind: something you learned about in class with something you saw in lab, or shadowing/volunteering/. Two great subsets of this are:

- you learn from a textbook what the inside of a mammal looks like, in general – heart, lungs, liver, etc, then you dissect or open up a lab animal and find the very same organs in the places where they belong. I don’t know why this is such a powerful experience, but it is, especially for textbook-oriented people.

- you learn about how a disease works on the molecular/cellular/organ level, and then you see someone who has that disease, and you understand how the symptoms you observe came to be.

Again, as with the people story, follow up the vivid hook paragraph with a background paragraph. If the story takes place in a lab, how does your story fit in with the overall purposes of the lab? Or how does it fit in with your overall desire to be a physician? If it happened in a clinical setting, tell us what you were doing there – were you shadowing, volunteering, scribing? Connect that up to your overall desire to be a physician.

Start thinking about how to arrange the stories

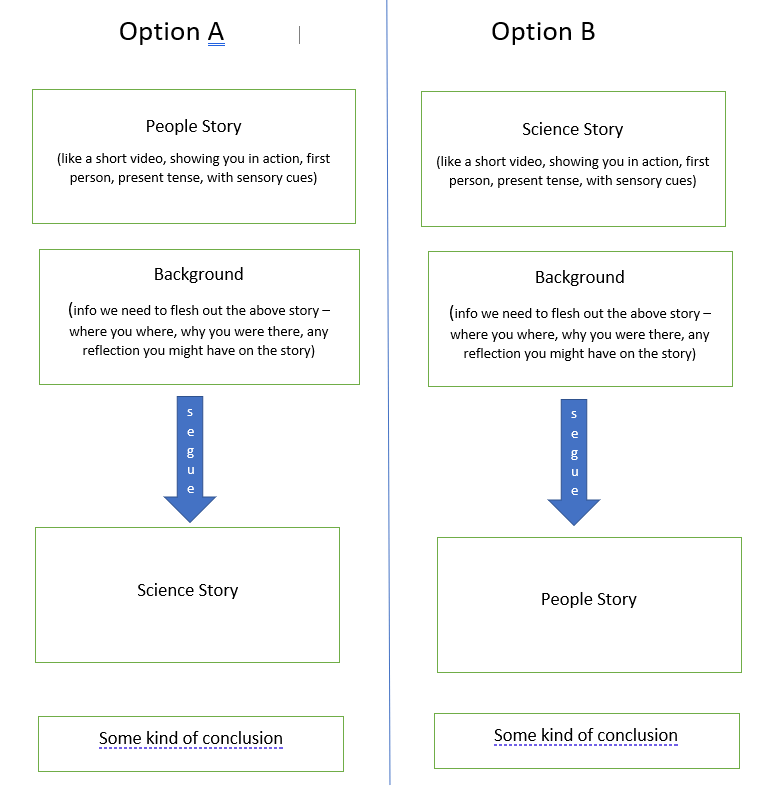

So now you have a draft of a people story and a draft of a science story. What’s next? Two options immediately present themselves:

My advice is to draft the two stories – the people story and the science story – and then experiment with Options A and B. Which order generates the best segue?

The Segue

Somehow you have to get from the people story to the science story, or vice versa. One way to do this is thematically:

- Science story about how excited you were in lab –

- Segue: You realize it’s not only about your result, but that the research will end up benefitting people

- Oh, yeah…people. People story

Or, the other way around:

- People story: you helped someone, got gratification from it

- Segue: You want to be able to do more than put a blanket around them – you want to treat their illness

- Science story

Or you could try a temporal segue:

- Either people or science story

- Segue: Later that semester, or the following summer…

- Either science or people story

Or a spatial segue:

- Either people or science story

- In the same building, but on another floor, or, on the other side of campus…

- Either science or people story

It may take many tries to find a segue that satisfies you. But keep at it – ahead lies the conclusion, and your segue will help you meet that final obstacle.

Get feedback – revise – get more feedback–revise again – get more feedback – revise, etc.

Show or tell your two stories to someone else and ask that person to help you find a link between them. Both stories are about you, and both are about medicine, so there’s a connection in there somewhere.

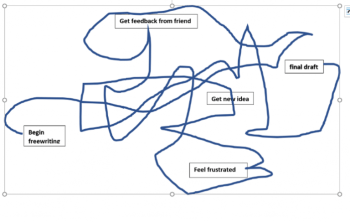

You may have been taught that the composition process moves linearly like this: first draft – revised draft – final draft – finished essay. In fact, most people’s experience looks more like the diagram to the right. That’s why you need to start early.

The Conclusion

Yes, this is a challenge. My advice is, don’t think about it until you’ve drafted your stories and come up with a segue. Your stories have SHOWN your personal experience of the two rivers. Your segue provides a thread linking them. Something about that link is what motivates you to pursue medicine. In your conclusion you can reflect on the relationship between that link and a) your desire to be a doctor b) the kind of doctor you want to be c) why you will be a good doctor d) your excitement about this next stage of your journey or e) values or ideals that are important to you. But keep it short. Prune your reflection to three to five sentences. If you are talking about your ideas, values or aspirations, link them to specific images you introduced in your stories. Keep generalizations to a minimum.

Now let someone close to you (parents, siblings, roommates, friends) read it all the way through. Do any of them say, after reading it, “Yup, that’s you.” Congratulations! You’ve shown what shape of snowflake you are accurately enough for it to be recognized.

Parting Words of Advice

- It’s going to be fine.

- This whole thing is just a marketing device to get you an interview.

- Start early in a low-key way, by finding your stories through talking, freewriting, daydreaming, recalling.

- Show your drafts to people you trust, and listen to what they say, but make your own decision.

- The medical school admissions people are not AGAINST you – you don’t have to prove anything to them in this essay – they just want to know something about you so they can have a natural-sounding conversation with you when they call you in for an interview.

- When in doubt, be authentic.

- Also, IT’S GOING TO BE FINE!